A case study for China and Poland -

The EU member states are required to put in place a significant transformation towards a low-carbon economy in order to meet the 2030 EU emission targets. Poland faces specific challenges due to its high reliance on domestic coal. The efforts undertaken by other coal intensive economies—like China—to reduce emissions could provide Poland with valuable lessons learned.

The EU has set ambitious emissions targets to face the threats from climate change. The 2030 EU climate and energy framework requires EU member states to reduce GHG emissions by at least 40% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, increasing the share of renewables in energy consumption to at least 27% and increasing energy savings by 27% compared with the business-as-usual scenario. This will require a significant effort by all EU countries in order to successfully transition to a low-carbon economy, while maintaining sustained economic growth.

In this context, Poland faces specific challenges in meeting the EU targets due to its high reliance on domestic coal. This raises the question of the efforts being undertaken by other coal intensive economies, how Poland compares to them, and what could be learnt from their experiences.

Poland is among the least emission-efficient economies in the EU, being characterised by the dominance of the power sector as a major driver of emissions, largely because of a high dependence on coal. In 2013, Poland contributed 9% of total EU emissions, ranking fifth among the most emitting countries in the EU28, after Germany, the UK, France and Italy. The Polish power sector in particular plays a crucial role in driving up the level of emissions. In 2013 the power sector was responsible for 54% of total Poland’s CO2 emissions from fuel combustion (IEA), with a carbon intensity of electricity and heat accounting for 633 gCO2 per kWh generated (in 2013; the second highest in the EU28 after Estonia).

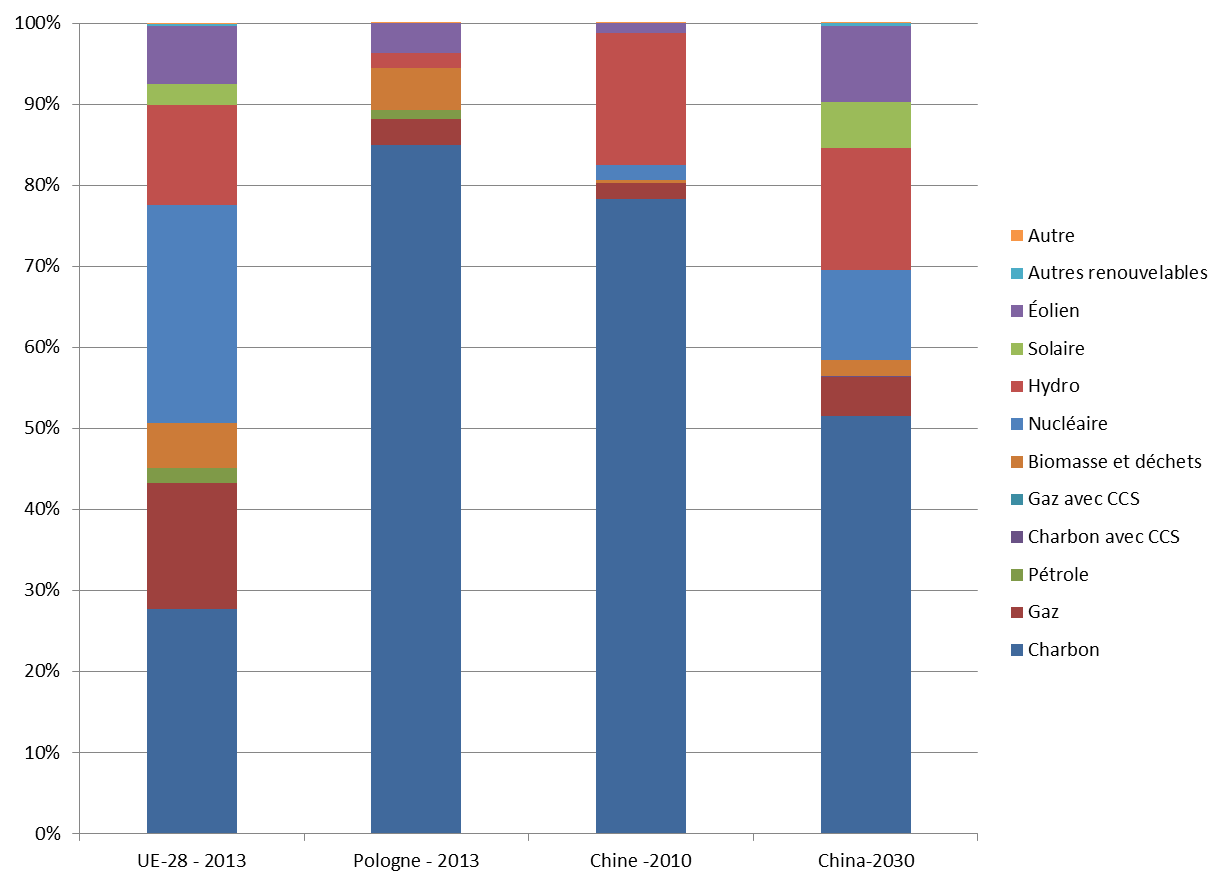

The high reliance on fossil fuels and particularly on coal for electricity production is the main driver of Poland’s high carbon intensity of electricity. In 2013 the share of fossil fuels in the electricity production accounted for 89%, a level far beyond the 45% of the EU28 Member States. Coal alone makes up about 85% of Poland’s power generation, versus a 28% of coal share in electricity in the EU28.

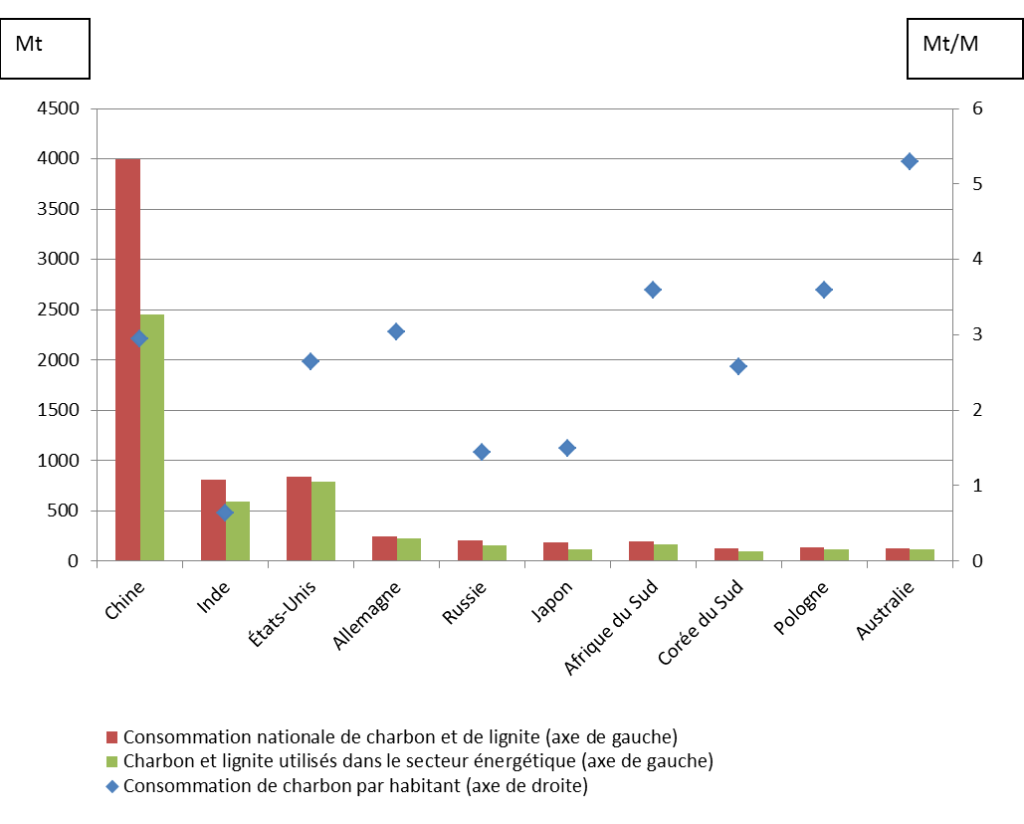

The high reliance on coal for electricity production makes Poland one of the biggest coal consumers in the world. In 2013 Poland ranked ninth in the world for coal consumption, with 87% of the total Polish coal consumption used in the power sector. When per capita coal consumption is taken into account, Poland ranks third after Australia and South Africa.

Figure 1. Coal and lignite consumption, top-ten countries, 2013

Source: Own calculation based on Enerdata and World Bank.

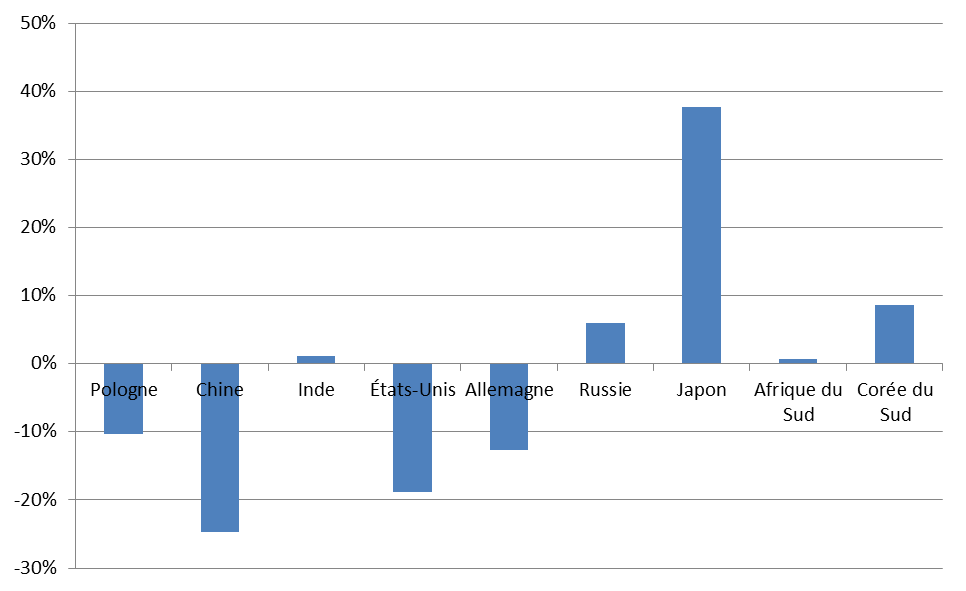

In the last 15 years the carbon intensity of electricity decreased in many high coal consuming countries. In Poland this trend is mainly due to a small replacement of coal with biomass, gas and wind in the electricity mix, while in China the increased share of gas and wind together with the introduction of nuclear power for electricity production explain the relatively high improvement in the carbon intensity of electricity.

Figure 2. Carbon intensity of electricity of top-ten coal consuming countries, variation between 2000 and 2014

Source: Own calculation based on Enerdata

Similarly to Poland, China has a very high carbon intensity of electricity and heat production, 679 gCO2/kWh in 2013, and a very high dominance of coal use in the electricity sector, about 75% in 2013. China submitted its INDC in June 2015, committing to reduce carbon intensity of GDP by 60% to 65% by 2030 below 2005 levels, increase the share of non-fossil primary energy to 20%, peak CO2 emissions by 2030 or earlier and increase the forest stock.

The analysis carried out by the MILES project (on future energy development and carbon emission pathways in five major emitting countries) shows that the implementation of the INDC1 targets in China could lead to a dramatic fall in the carbon intensity of electricity, by 40% between 2010 and 2030, while ensuring a simultaneous increase of the electricity production, which more than doubles between 2010 and 2030, increasing from 4,193 TWh in 2010 to 9,405 TWh in 2030. The growth in power generation is a necessary condition to meet the increasing energy demand driven by a growing population, predicted to peak around 2030, and a fast pace of economic growth.

Figure 3. Electricity generation by fuel

Source: Own calculation based on Enerdata for EU and Poland; and MILES project for China.

The transition of the power sector in China is made possible by a reduction of the share of fossil fuels without CCS, which reduce down to 56% in 2030, accompanied by an increase in the share of renewables in total power generation up to 32% in 2030 and an additional 11% contribution in total power generation by nuclear power.

The decarbonisation of the power sector appears being a crucial condition as, according to the MILES report, the electrification rate of China will increase from 18% in 2010 to 21% in 2030 and electricity will become a major energy source in the final energy consumption. According to the authors of the report, the high penetration of non-fossil fuels in the Chinese power sector in 2030 will be made possible by continuous support policies and measures, including inter alia, efforts for reducing the cost of non-fossil fuels, higher priority on newly-built non-fossil power plants and feed-in tariffs for renewable power plants.

The Chinese INDC scenario demonstrates the feasibility of a transition from an electricity sector highly dependent on fossil fuels, particularly coal, to a low-carbon power sector. The analysis carried out for the MILES project shows that this transition can follow different decarbonisation strategies according to the country specificities. In the case of China, the transition scenario is based mostly on the deployment of renewables and nuclear. For Poland, the potential decarbonisation strategies (e.g. nuclear development, renewable energy sources [RES] deployment, natural gas imports) will have to take into account the specific features of the Polish economy and energy system, where energy security will play a crucial role. Furthermore, the Chinese example demonstrates that the transition is feasible also in a context of a growing economy with an increasing energy demand. This is a crucial point for a country like Poland who aspires to expand its economy and catch up with high income countries.

1In preparation for the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP21), hold in Paris in December 2015, countries have agreed to publicly outline what post-2020 climate actions they intend to take under a new international agreement, known as their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs).