The European Commission published on July 20, 2016, its proposal for the so-called Effort Sharing Decision (ESD), setting national GHG mitigation targets for sectors not covered by the bloc’s emission trading scheme. It applies to roughly 60% of GHG emissions in Europe mainly from the building, transport and agriculture sectors. Just out, the current proposal is based on the EU-wide GHG emissions target pledged by the EU at last year’s Climate conference that led to the Paris Agreement, but is not in line with the contemplated timeline to revise the level of global ambition. Proposed national targets are differentiated according to the level of economic development and contain several flexibilities that give Member States the freedom to reduce their sectoral efforts. At a time of uncertainties, a reassessment of the EU ambition level would be beneficial to translate political targets into efficient national and local policies.

GHG emission: sharing distribution and flexibility mechanisms

The Effort Sharing Decision (ESD) divides between Member States an EU-wide 2030 GHG emissions reduction target compared to the year 2005 for sectors not covered by the Emission Trading System (ETS). It is aimed to achieve a reduction by 40% of total GHG emissions compared to 1990 in the EU which was the objective decided at the European Council of October 2014 and brought to the table at last year’s Paris climate conference. In practice, EU countries are required to meet each year between 2021 and 2030 an annual carbon limit and would face a penalty on their following year’s obligation in case they fail to do so during one year. Some flexibility is given to them as they can bank unused emissions limit for the future or borrow in advance allowed emissions in the future up to a certain limit in case they exceed their emission limit during a year. Transfers between countries are also allowed. The European Commission will officially monitor the progress of Member States every five years.

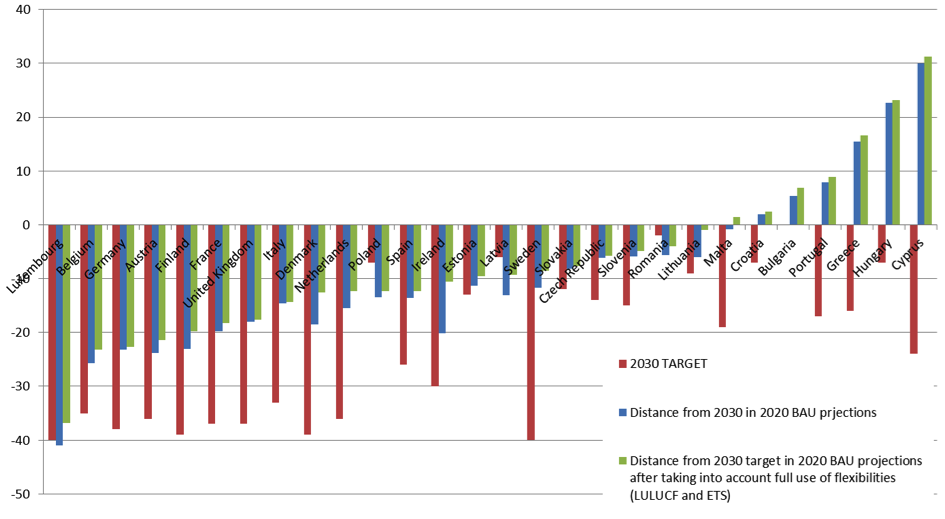

Similarly to the ones adopted for 2020, national targets are based on relative GDP per capita in order to give stronger targets to richer countries. Higher income countries targets are also adjusted according to an evaluation of their emission reduction potential. Compared to 2005 emissions level, proposed national targets go from -40% for Sweden and Luxembourg to 0% for Bulgaria (see Figure 1 below) and stronger targets apply to Western and Nordic European states (Germany has a -38% target, France and the UK -37%) whereas Eastern European countries have smaller headline targets to achieve.

“Business-as-usual” projections

If we consider 2020 “Business-as-usual” projections made by the European Environmental agency, the picture becomes slightly different. These projections take into account recent emission trends and existing measures and can be used to evaluate the level of effort and additional measures required in the decade from 2020 to 2030. The pressure is still higher for Western and Nordic countries, but it is reduced by emission reductions that will have taken place since 2005. By contrast, countries most affected by the economic crises and most Eastern European countries will already be close to or over their objective. For 12 countries, proposed targets will mean reducing their emissions by 8 % in 2005 emissions and six countries would be allowed to increase emissions between 2020 and 2030 even before taking into account any flexibility option (see Figure 1). Poland, Romania and Latvia will be farther away from their 2030 target in 2020 because their ESD emissions increased since 2005, but by rather small relative amounts.

Figure 1. National GHG emissions targets for non-ETS sectors relative to 2005 emissions and distance to the target in 2020 BAU projections, with and without use of new flexibilities (in %)

Figure 1. National GHG emissions targets for non-ETS sectors relative to 2005 emissions and distance to the target in 2020 BAU projections, with and without use of new flexibilities (in %)

Source: European Commission and With existing measures scenario in ”Trends and Projections in Europe in 2015", EEA

Using emissions cuts form other sectors: New flexibility provisions

In addition, Member States are given new possibilities to use emissions cuts from other sectors to fulfil part of their obligation. These new flexibility provisions are of two sorts:

- one allows every country to use an amount of emission cuts coming from land-use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) according to the relative size of their agriculture sector. In the event that all countries use completely their LULUCF flexibility provision, 280 MtCO2 eq. could be achieved outside non-ETS sectors perimeter over the 2021-2030 period, the equivalent to relax the overall non–ETS target by 1% to 29% compared to 2005 levels.

- The second flexibility provision allows nine relatively high income countries to cancel ETS allowances and take it into account in their obligation for non-ETS sectors. It is also limited to an overall 100 MtCO2 and eligible countries will have to decide before 2020 if they want to use it and to what extent for the full period. Assuming full use of this flexibility option will have the same effect than a further relaxing of the non-ETS target by 0.34%. Therefore, the overall impact of flexibility provisions on the stringency of non-ETS cap is not that important (1.3% of 2005 emissions approximately), but could be significant at a national level: it represents almost 10% of 2005 Ireland’s emissions, or one third of its non-ETS 2030 target (see Figure 2).

Effort Sharing Decision’s targets compared to the Paris Agreement’s longer-term goals for GHG mitigation

At another level, it is important to evaluate the coherence of the decision with global efforts to mitigate climate change. To this respect, the decision mentions the Paris Agreement and, in particular, its revision mechanism:

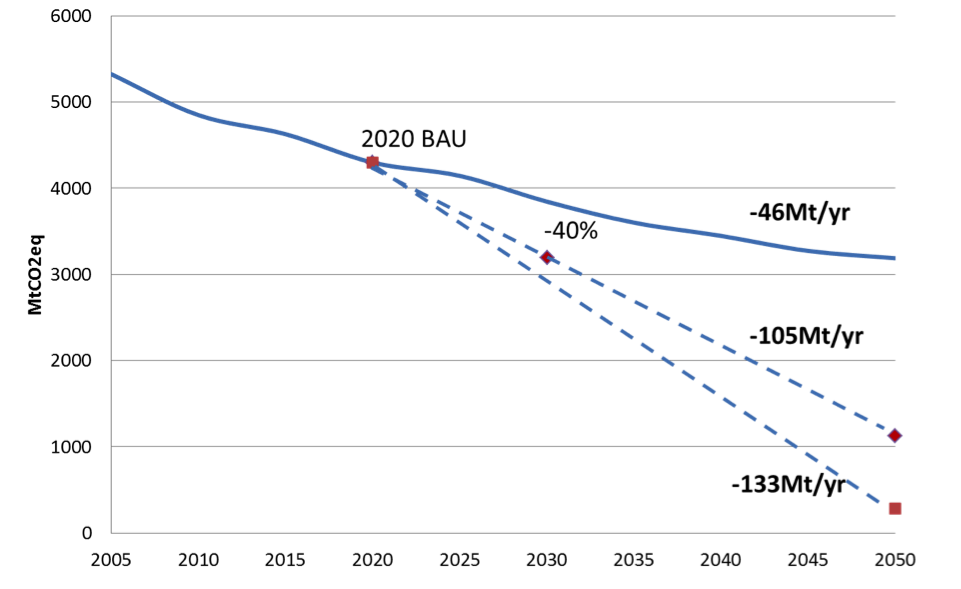

The European Union and all other Parties are obliged to communicate nationally determined contributions every 5 years, informed by the Agreement's global stocktake taking place in 2023 and every five years thereafter. (see page 2)Accordingly, a review of all decision elements is planned before February 2024 to prepare for a possible revision of the level of ambition for 2025. This ignores completely the possibility for Parties to increase already in 2020 their pledge for 2030 after the facilitative dialogue on mitigation in 2018. The Paris Agreement requires Parties to collectively limit temperature increases below 2°C and to aim for 1.5°C. However, current EU’s target is in line with a GHG emission reduction of 80% (see Figure 2) and corresponds to a likely increase of 2°C or more in most recent UNFCCC scenarios (see table SPM.1 here). The EU as other Parties will need to increase its ambition with time to achieve long term climate goals.

Figure 2. Historical and BAU GHG emissions in the EU vs. 2030 and long term targets (-80 to -95% in 2050)

Figure 2. Historical and BAU GHG emissions in the EU vs. 2030 and long term targets (-80 to -95% in 2050)

Source: Iddri from EEA report “Trends and projections in Europe in 2015”

To conclude, it is useful to remember the purpose of these national targets which are meant to “(…) provide the incentive for further policies driving deeper reductions”. Sectoral policies are not yet sufficient in Europe to reach long-term mitigation goals as highlighted by the business-as-usual emission trend estimated by the European Environmental Agency in Figure 2. It seems clear that the pace of transformation has to accelerate in Europe to be on track to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goals. The transition has even to start if we consider the transport sector covered by this decision and represents one quarter of EU’s GHG emissions. However, one could question the political message sent through the ESD proposal by the European Commission to Member States. A cocktail of moderately ambitious targets, new flexibility provisions and a faraway in the future revision could be the perfect excuse for many of them to kick the can down the road. At a time when Europe’s future is getting cloudy, an ambitious message on collective action would certainly be useful. A first step in this direction would be to provide the means for an earlier revision of national targets to pave the way for an increased EU climate ambition in line with the goals set by the Paris Agreement.