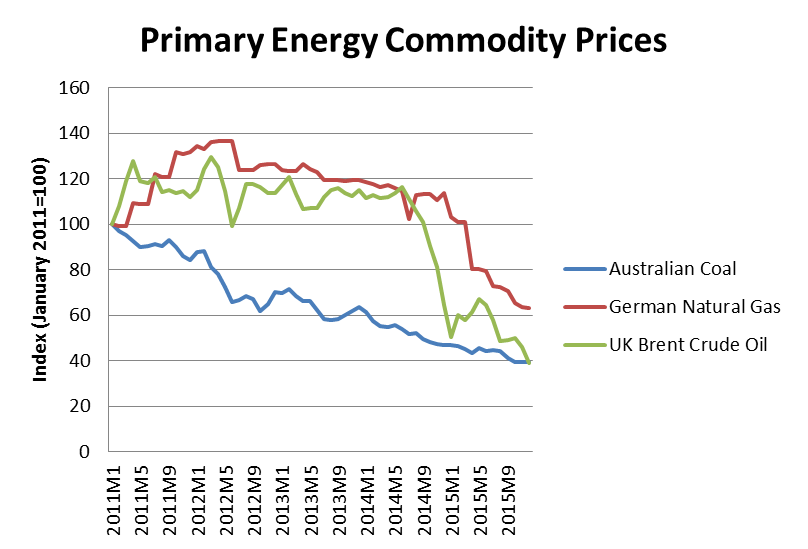

The drastic fall in global oil prices has received a fair amount of attention of late. However, while oil has been capturing the headlines, other carbon intensive fuels have also been experiencing equivalently impressive price falls. What might this mean for climate policy in Europe, especially this year when the EU will revise its policy framework for the promotion of renewable energy technologies?

The figure below shows an index of international thermal coal prices, crude oil prices, and EU natural gas spot prices (based on Russian import prices to Germany) over the past 5 years up until December 2015. The figure shows prices have all fallen drastically from their 2011 levels—by 60%, 60% and 40% respectively.

Source: IDDRI, IMF

This also seems like a phenomenon that will stick around for a while. The International Monetary Fund notes that fossil fuel prices are likely to stay "lower for longer" for several reasons. In the case of coal, this is linked to the drastic slowdown of economic growth in major emerging economies like China (which consumes half of the world’s coal) and a legacy of massive overbuilding of new capacity during the boom on the supply side. In the case of European gas, prices are expected to stay low for a while since much gas is still sold on oil-price linked contracts and oil is expected to stay low for some time. The discovery of large new gas plays off the coast of Egypt and in Argentina, and slower growth in demand, are expected to contribute to this long-run trend.

These price trends matter for climate policy because they are key determinants of the wholesale prices of energy for power, heating and cooling, and transportation. To be sure, they are not the only determinants of these prices—for instance, falling electricity prices also reflect production overcapacity, which is in turn linked to slowing demand, overbuilding during the boom, and a short-run consequence of needing to inject renewables into the system before other plants are ready to retire. Nevertheless, lower fossil fuel prices compound these effects.

As for European climate policy in 2016, this “reality check” of “lower fossil fuel prices for longer” has very concrete implications. Europe is currently in the process of revising its policy and legislative frameworks to support renewable energy technologies and their integration into the market post-2020. One of the key debates in this context is: what should be the role of state support for renewable energy post-2020, when current state aid guidelines expire?

For its part, DG Competition, the EU’s directorate in charge of competition policy made its objectives clear in its revision of economic support rules in 2014. It stated:

“These Guidelines apply to the period up to 2020. However,…it is expected that in the period between 2020 and 2030 established renewable energy sources will become grid-competitive, implying that subsidies... should be phased out in a degressive way.” (Cf. Paragraph 108 of Article 3.3.1)

Energy prices in 2030 are too far away to make reliable predictions about. However, in light of recent fossil fuel and power price trends, the project to begin to phase out state supports for renewables from 2020 now looks increasingly unrealistic.

The only way this timeline could be kept would be if the EU experienced an unexpected surge in the level of its carbon prices, as this could help to offset the loss in competitiveness from the removal of the support schemes. Unfortunately, that seems unlikely. The price that companies pay to emit CO2 under the EU’s carbon market remains far too low, at just 7€/tonne of CO2. Most market analysts think prices will not rise to meaningful levels for at least the next decade or so. Meanwhile the level of other carbon and energy taxes remains low and uneven across Europe. Some Member States have begun to increase them for the sectors outside the EU carbon market, which is desperately needed. But they will still need to rise a lot in a short period of time to make up for the recent falls in fossil fuel prices, let alone stimulate investment in low-carbon technologies.

Some sector-specific measures—such as quickening the retirement of old and inefficient baseload coal power plants—can help in the electricity sector and should also be pursued more vigorously. But there is a risk that these measures will take some time to play out, and they only apply to electricity.

Finally, even if energy and carbon prices rebound unexpectedly, the volatility of these prices will pose a problem for investors looking for a secure return on their investment in exchange for low-cost finance. EU rules around long term contracting are currently not clear enough to respond to this challenge and need further clarification.

There is no question that to be a politically durable solution to climate change, renewable energy technologies will need to be gradually integrated into energy markets at energy market-determined prices (that correctly price CO2 and other externalities). Thus, more needs to be done to raise CO2 prices and taxes to price these externalities fully into the market, and ensure a favourable market design to mitigate important investment risks. However, until these conditions are properly set, Europe needs to proceed cautiously in phasing out otherwise very effective support schemes for renewables. The recent volatility of energy prices is a timely reminder of that fact.