India released its INDC on the 2nd of October, a national holiday to celebrate the birthday of Mahatma Ghandi. The choice of date is interesting as it shows the desire of the Indian government to get domestic political mileage out of this important announcement. Compared to the toxicity of international climate policy in India several years ago, this shows how the debate has evolved.

Here we provide a first reading of the Indian INDC.

Does the INDC represent an acceleration and strengthening of climate action within the country?

India’s INDC contains a number of qualitative aspirations, and three quantitative targets:

- To reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 33 to 35 percent by 2030 from 2005 level.

- To achieve about 40 percent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel based energy resources by 2030 with the help of transfer of technology and low cost international finance including from Green Climate Fund (GCF).

- To create an additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover by 2030.

A 33-35% improvement in GHG intensity will require a continuation of current trends, broadly speaking. India’s Copenhagen pledge is for a reduction of its GHG intensity by 20-25% by 2020, compared to 2005 levels. By 2012, GHG intensity had been reduced by 13% from 2005 levels, a rate of -2.03% per year (data from CAIT, excluding land-use). Continuing this annual rate to 2020 would reduce GHG intensity by 26%. So India appears on track to achieve its Copenhagen pledge. Simply projecting forward this rate of GHG intensity improvement to 2030 would see a 40% improvement against 2005 levels.

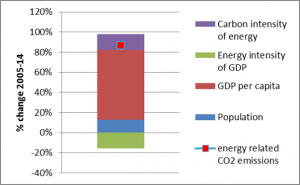

It is notable, however, that India has not been reducing at the same rate its energy related CO2 intensity per unit GDP over the past years (-2.14% in total 2005-2014). As India industrializes and urbanizes, it has and will shift away from traditional biomass and towards industrial sources of energy, notably coal. The graph below decomposes changes in Indian energy related CO2 emissions over the period 2005-14. Continuing to reduce the GHG intensity of the Indian economy in line with its INDC will thus require action on its energy mix.

Source : Indian INDC - IDDRI

Source : Indian INDC - IDDRI

It is in this spirit that Indian INDC proposes also a target for non-fossil fuel capacity in the electricity mix (40% by 2030). It should be noted that this is installed capacity, not production – with a lower capacity factor for renewables, the share of non-fossil fuel generation in electricity production in 2030 would be lower. Currently, non-fossil fuel capacity is at 24%, so increasing this to 40% would imply a significant effort. Taking the projected level of electricity demand in the Indian INDC, making assumptions for grid losses (15%) and total capacity factor (45%) we can estimate that total non fossil capacity would have to reach about 290 GW in 2030 to be 40% of total installed capacity. With renewables plans of 175 GW (2022) and nuclear plans of 63 GW (2032), incremental non-fossil capacity of about 53 GW would need to be developed by 2030. Some of this will probably come from hydro (about 40 GW today, and a potential estimated in the INDC at 100 GW).

So the most defining aspect of the 40% non-fossil capacity appears to be recently announced, but not yet implemented short-term plans on renewables to 2022 and longer-term plans on nuclear to 2032. Its INDC builds on these but doesn’t necessarily require going further.

Does the INDC contain clear and credible information about how the contribution will be achieved, and the transformations it requires?

When looking at its constituent elements, India’s INDC is overall very transparent: key information such as the target growth rate, the sectors covered, target electricity demand etc. allow one to reconstruct well the implications of the INDC for India’s overall emissions and more granular implications for the energy sector, for example.

How does the INDC articulate with the domestic development priorities of the country?

In the supplementary information to its INDC, India clearly articulates its development vision: a ten percentage point increase in urbanisation; a 3 fold increase of GDP/cap with a 7% growth rate; and an increase in electricity demand by a factor of 3.2. It makes a cogent case for India’s vulnerability to climate change. It describes India’s extremely low emissions per capita (1.56 tons) and GDP/cap of just 1408 USD. The INDC rightly states that India has been able to achieve a high level of human development (measured by the Human Development Index) with such a low GDP per capita. The INDC’s emphasis on the electricity sector underscores the importance of providing power to a country with 300 million citizens without access to electricity.

India’s INDC places a lot of emphasis on the financial challenge of implementing stringent climate policies and achieving development objectives. India has a relatively low investment as a share of GDP (31.5%) given its development stage; it has a current account deficit of 1.4% of GDP meaning it lacks a trade surplus that can be invested strategically in the economy. According to the World Bank, Indian infrastructure would require about 1.7 trillion USD in investment in the coming decade. As the FT noted in its recent special on investment in India: “…private sector investment has virtually ground to a halt. The cost of capital is high, and banks are reluctant to extend credit because they have too many bad loans”. The international community certainly has a role to play in helping India to fund its development aspirations; and the returns could be very high. But increasing international public and commercial investment will require a lot of effort to improve the regulatory environment. Policy cooperation in the future could focus on this domestic and international investment challenge.

To a large degree, the India of 2030 remains to be built and born. Enormous demographic, industrial, urbanisation, and technological transitions are underway. In this context, crucial drivers of a lower-carbon society in India are related to India’s development model itself, not necessarily to its energy choices although these are crucial too. This has been concretely explored in the India report of the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project, which contrasts two alterative development scenarios: ‘Conventional decarbonization’ and ‘Sustainable’. The Sustainable scenario is based on structural policies such as smarter urbanisation, resource efficiency, investments in human capital and so on. It results in a more cost-effective transition for India. Capturing such profound development choices in India in an INDC is probably too much to expect – the level of detail provided on the development strategy is already impressive. But rather than looking at the precise numbers in the INDC, what is positive is that it at least starts to sketch out a broader vision for a new, low carbon development model.

What are the barriers and opportunities for going further?

Overall, therefore, India already has some ambitious aspirations for the shift to a low-carbon economy, notably its renewables plans in the electricity sector. Its INDC builds on these but doesn’t necessarily go further. India is a developing country with low emissions per capita and GDP per capita. Nonetheless, with so much growth and infrastructure investment yet to occur India’s choices today will be crucial for its long-term emissions trajectory and that of the world. In this regard, while the INDC establishes a basis, there are still risks of locking into a higher emissions trajectory. Crucial domestic choices such as urban planning, infrastructure choices, approaches to development objectives such as local air pollution and social inclusion will need to be resolved alongside international cooperation on financing and technology availability.