The economic transition underway in China is desirable, even if it contains significant risks and new challenges for Chinese climate policies. China will indeed soon be reaching (or has already reached) peak coal. Yet drivers of strong investment in coal power continue. In the long term, the policy challenge in China will shift from stopping new coal to closing existing coal, and addressing the social, economic and political challenges that go with this.

China’s largest coal producer, Shenhua, has just announced a series of write-downs on its coal production, processing and power plant assets. This comes on the back also of an announcement at the end of 2015 by China’s National Energy Agency that China would not approve any new coal mines for three years, and would close thousands of small mines.

What is driving this, and what does it mean for Chinese policy and implementation of its ‘nationally determined contribution’ under the Paris Agreement?

The Chinese economy is slowing considerably. Real GDP growth was reported at 6.9% for 2015, the slowest in several decades. In short, the Chinese economy has been growing on an economically unsustainable model of very high investment, infrastructure build out and credit growth. It is now starting to slow and restructure. It seems highly likely that this represents a structural trend break.

This in turn is having a significant impact on the Chinese electricity sector. As major consuming sectors like steel slow and even decline, so has total electricity demand. Total Chinese electricity demand is estimated to have fallen by 0.2% in 2015, compared to 2014. Again this compares to a trend of 10% annual growth since 2000.

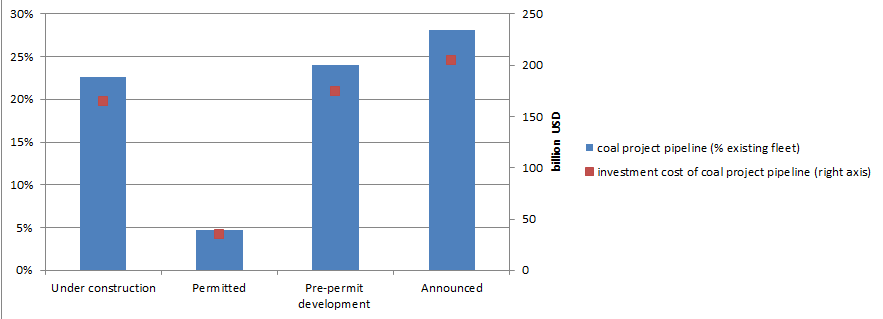

In turn, the capacity factor of the Chinese coal fleet has been falling significantly, and was down to 53% in 2014, and certainly fell significantly further in 2015 (between 47% and 50%). In simple terms, a lot of Chinese coal plants are not being used very much. Against this trend, however, there continues to be investment in coal power (see Figure 1 below). This represents a potentially stranded investment cost of $164 billion, or 1.6% of total Chinese GDP in 2014. Yet many more coal plants are in various stages of planning.

Figure 1. Coal pipeline compared to existing fleet and investment cost

Sources: data on existing fleet from Enerdata, data on pipeline taken from Global Coal Plant Tracker, unit investment cost for coal in China from IEA (2015), "Projected Costs of Generating Electricity".

The risk of stranded assets in the coal sector can be further highlighted by looking at Chinese clean energy aspirations. The drive to clean energy is being driven by concerns of climate change, energy security, and local air pollution. The share of all non-coal electricity has grown by 6 percentage points between 2011 and 2014. China has a target of 15% non fossil fuel energy in primary energy supply by 2020, and 20% by 2030. This would equate to a non-fossil fuel share of electricity of about 34% by 2020, and 44% by 2030. In the energy system scenario developed by the University of Tsinghua as part of an IDDRI-led project, primary energy consumption of coal remains essentially stable in between now and 2030.

What conclusions can be drawn from this for China’s implementation of the Paris Agreement?

It appears increasingly likely that China will overachieve its 2020 CO2 intensity target, and be well on the way to overachieving its 2030 target and peaking its emissions earlier than 2030 (for a further academic justification of this, see here). The slowdown and restructuring of the Chinese economy will bring significant improvements in energy intensity—a point made by BP in its annual energy outlook yesterday. If this is the case, historical trends for CO2 intensity improvement may be too conservative. Watch out for signs in the 13th Five Year Plan (FYP), to be released this year, confirming that China will exceed its 2020 target. If China signals that it is well on the way to overachieving its CO2 targets, this could breathe life into the Paris Agreement’s mechanism for regularly increasing ambition.

Some might say that this represents the ‘right result’ (less CO2) for the ‘wrong reason’ (less growth). This point overlooks the extent to which China’s previous growth model was unsustainable. The economic transition underway is desirable, even if it contains significant risks. What is certain is that the ‘New Normal’ context will create some new challenges for Chinese climate policies. The above analysis strongly suggests that China will soon be reaching (or has already reached) peak coal. Yet drivers of investment continue, as seen in the above discussion of the coal project pipeline.

The long lead time between project development, approval and implementation mean that capital intensive industries, like power generation, are historically prone to cycles of overinvestment. This ‘natural cyclicality’ is probably exacerbated in the Chinese context. The political drive for growth, the distortions of market incentives in the allocation of capital, have driven significant wasteful investment across the whole economy (Chinese researchers estimated that ‘wasted investment’ accounted for half of total investment across the whole economy in the period 2009-2013).

There is thus a real risk of a similar investment bubble in coal capacity (indeed, the bubble may already exist). Policy incentives and regulations to stop coal investment appear urgently necessary. In the longer term, the policy challenge in China will shift from stopping new coal to closing existing coal, and addressing the social, economic and political challenges that go with this.

At the same time the risk is that economic turbulence leaves less political and financial capital to devote to climate policy. China will not wean itself off infrastructure investment over night. Investment in environmental and climate protection could allow for continued productive investment, absorbing some of the decline in investment in other, oversupplied sectors (like steel, cement and coal power). Clean air is one thing not in oversupply in China! Fiscal reform such as carbon pricing could be used to dampen investment in oversupplied, carbon-intensive sector. The revenues could be recycled to promote economic restructuring and greater equality. In short, the economic slowdown also presents China with an opportunity to combine economic and environmental transition.

Image source : Pixabay